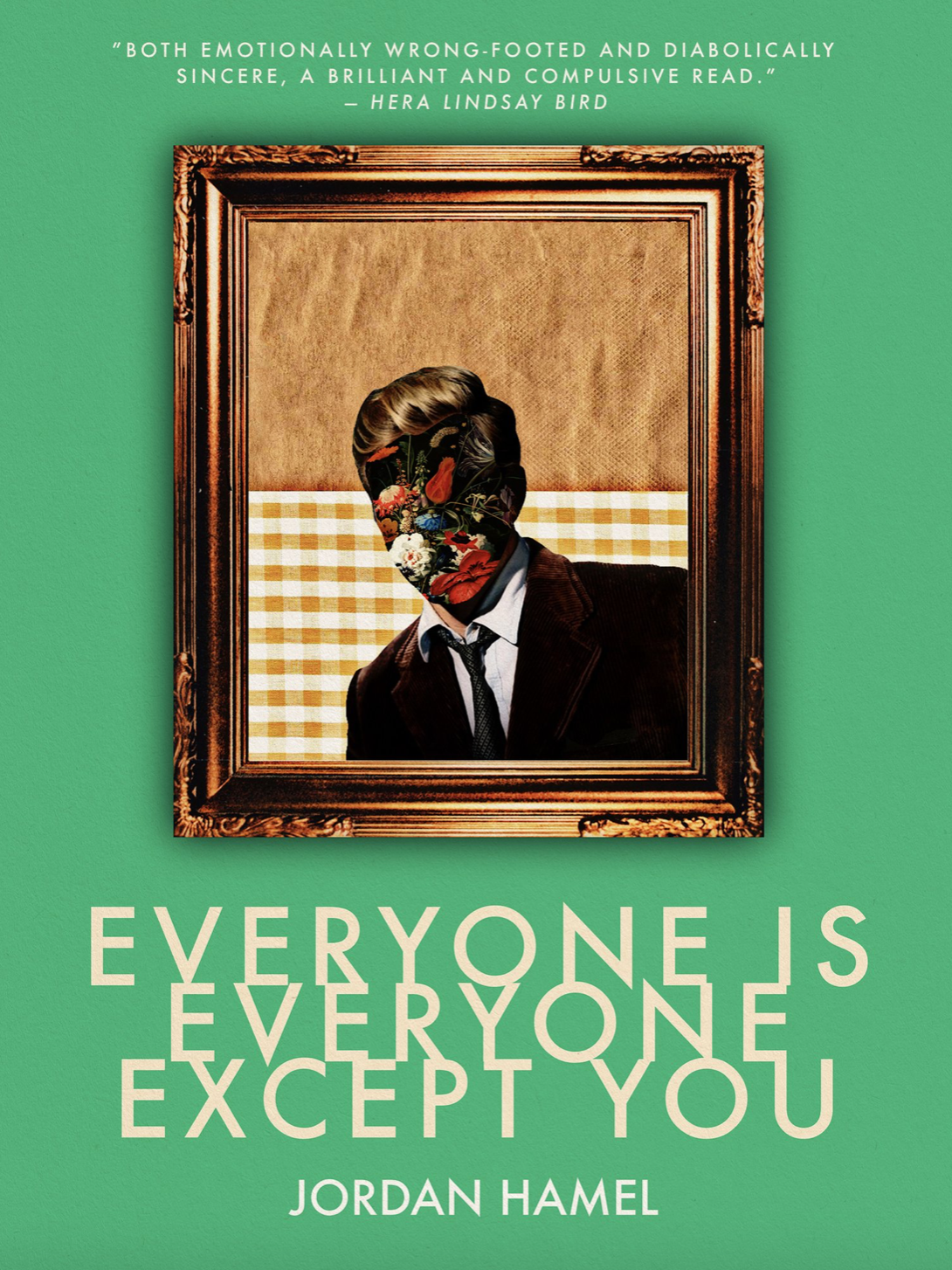

Everyone Is Everyone Except You by Jordan Hamel

In Everyone is Everyone Except You (2022), Jordan Hamel is unafraid of his worst self. Hamel understands the feeling of misshapenness that can only be satisfied with the perfect niche pop culture reference or an overdone cliché that is then overdone some more.

This is Hamel’s debut poetry collection. He was Aotearoa New Zealand’s Poetry Slam Champion in 2018 and his poetry, essays and stories have been published and received various accolades, including third place in the prestigious Sargeson Prize in 2021. Hamel’s formal dexterity is evident throughout this collection and his background in performance poetry clearly a strength on the page.

Everyone is Everyone Except You revels in contradictions. It is precise in its awkwardness. The opening poem, ‘The worst thing that will happen to you hasn’t happened yet’, feels like the soliloquy at the beginning of a Shakespeare play. Hamel is telling us how to read his book, guiding us as readers on a carefully curated emotional journey. This poetry collection is one which should be read start to finish to properly experience this journey. Hamel is in control and he likes it. Everyone is Everyone Except You is greater than the sum of its parts.

The book is broken into five parts which are loosely thematic – I read them as masculinity/religion/romance/career/self – but of course each section overlaps all these categories and defies definition. My favourite section was ‘Everyone is having sex and meaningful relationships except you’ but there were wonderful moments throughout.

The poems’ narrators are self-deprecating, mediocre, closeted and bitter, sad and afraid but the poetry is none of this. The poetry is also joyous and funny, deeply caring and loving. (Full disclaimer: I once worked in an office with Hamel and we all thought he was dead inside.)

Hamel skilfully satirises every version of himself: small town escapee ex-catholic reality TV addict depressed sports fan corporate slave professional managerial class nightmare. The cultural references dig deep into the recesses of an aging millennial mind and scratch an itch inside your brain you didn’t even know was there. But Hamel constantly surprises:

some mermaids are actually

middle aged accountants named Stephen

dreaming of a land-view holiday home.

I saw a school of Stephens the other day

out of their habitat just talking inhaling IPAs

inhaling each other

tail stuffed tuxes pleated smooth

Truly the highlights in this book for me were poems where the narrator is in love. Hamel writes about heartbreak but he also writes about happiness. Happiness in-spite-of; happiness because-of. He gives us sadness disguised in vulgarity that switches into jokes which surprise, then sincerity which surprises even more. Hamel knows how to break through carefully constructed sincerity to elicit real laughs from a reader. I suspect it’s in performing where he honed his comedic timing – his understanding of an audience shines in the funnier moments of the book.

‘When you leave take the Netflix account with you’ would make me cry if not for the second-to-last stanza:

I wish my ass was a USB port.

I wish all the world’s content could be

systemically pumped into me. I wish

I warranted repeat viewings.

This motif of mediocre protagonist in love is charming. ‘I’ve spent too much time thinking about running away with you’ declares: ‘but where would we even run to? Carterton? I’m in terrible shape.”

Hamel relies on a shared cultural knowledge to set up his poems but never takes us where we expect. ‘You’re not a has-been you’re a never was!’ is a personal favourite, (‘scribbling little lies in the margins of our days/is exhausting and historically underfunded.’) with sentiments echoed later in ‘The Simple Life’ (‘let’s show them all we can last, we can/join a startup incubator as endurance art’). The whole book is a tightly woven masterpiece of cynicism and sincerity (‘test out your tight five at climate marches and memorial services’) and Hamel’s clever control of form and structure is consistently thrilling throughout.

If you’ve ever shared a Netflix account, swiped on Tinder, gone to work hungover, felt like an overgrown teenager, or turned thirty against your will, then this book is for you.

Grace Tong is a writer from Aotearoa New Zealand now living and working on the land of the Wurundjeri people. Her short fiction has been published in various places, most recently in Aniko Press and takahe magazine.