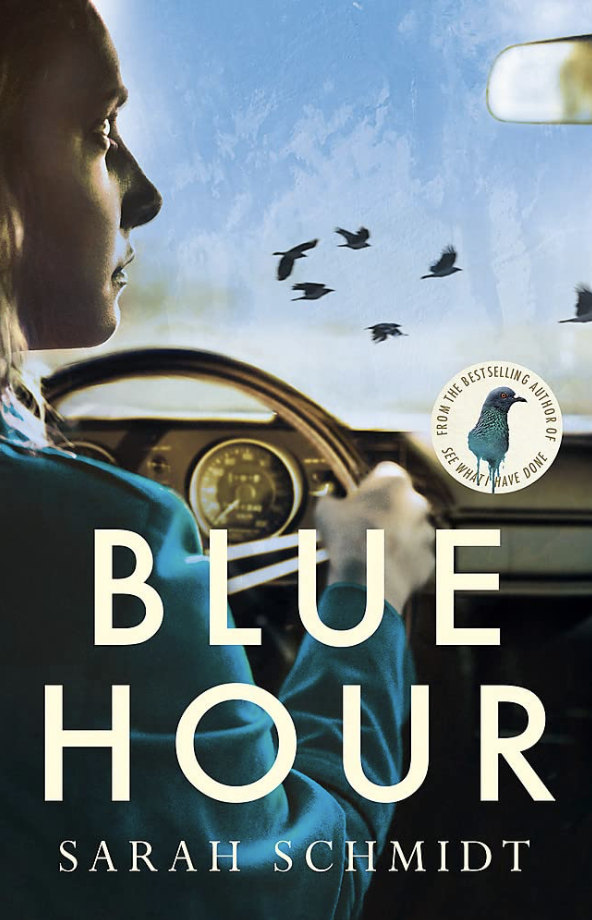

Blue Hour by Sarah Schmidt

“I will never be like my mother.”

It’s an age-old declaration that teenage girls make: an assertion of limited power on their path to adulthood. I said it many times when I was young, reaffirmed it as I found my own way in my twenties, and now, middle aged and mother to three, I’m starting to see how hard it is to keep. It’s also the premise of Sarah Schmidt’s second novel Blue Hour (2022), following her 2018 award-winning bestseller See What You Made Me Do.

In Blue Hour, mother-daughter duo Kitty and Eleanor navigate motherhood in a dual narrative that spans the course of forty years. It starts with Kitty in the late 1930s as she breaks away from her conservative parents in a quest for independence, and runs all the way to the late 1970s when her daughter Eleanor becomes a mother herself. The blue hour refers to the twilight period when the sky takes on a mostly blue shade, which Schmidt uses as a metaphor for motherhood. “Blue isn’t as common in nature as you would think,” Eleanor says to her daughter in the opening chapter, a premise for all that is to come between Kitty and Eleanor.

The story is fragmented through the years as we learn the reasons why Kitty failed to be the mother Eleanor needed her to be. “Mother; this island,” Schmidt writes, the great paradox of troublesome mother-daughter relationships. So desperate for a mother’s love, Eleanor does anything to glean Kitty’s support, including marrying a man Kitty pushes on her, a man Kitty thought she would have liked to marry instead of the broken WWII veteran she was left with.

In the beginning, you can’t help but empathise with Kitty, but her inability to process her grief after a tragic loss in the family, and the ways in which it affects her relationship with Eleanor, makes you soon despise her.

Eleanor’s rocky relationship with Kitty has made her vow to be a better mother to her own daughter, Amy. Yet motherhood isn’t something she was ready for: it was physically forced on her by an abusive husband before he was drafted to Vietnam. Alone and in the foggy haze of first-time motherhood, Eleanor leans on Kitty for support, who’s more than happy to relive her own failed attempts at the job. “The early years of parenting are dangerous, make you believe that you deserve the entirety of your child because they wouldn’t exist without you. But now Eleanor knows the real danger: the inability to register that the new version of yourself can’t exist without them. The cruelty of ownership.”

Eleanor is left shocked when Kitty crosses one too many boundaries, and finally cuts ties with her after a lifetime of emotional abuse. But as the story draws to a close, the reader and Eleanor herself realises she’s more like her mother than she thought. It’s when she says to Amy, “‘Did I ever tell you crows pass on their memories? They pass all their collected thoughts and knowledge down the generations for survival.’ For love. There is no telling what has been passed down to me, to us,” that you realise the apple hasn’t fallen far from the tree.

As with the character of Lizzie Borden in Schmidt’s first novel, she captures the voices of Eleanor and Kitty using visceral descriptions and repetition to get inside the head of two women who are both determined to do better but are lost in their inability to overcome the past. “The past made her feel good inside, like she had something to look forward to, something that could be the present,” Kitty muses at one point. Kitty is that character readers love to hate, a maternal yet narcissistic bully, while the reader is left yearning for Eleanor to find the love she so desperately craves, and the love she was denied by the one person who was supposed to offer it unconditionally.

It’s a relatable read with reflections on motherhood that will hit home for many. “The arrival of children is the departure from yourself,” Schmidt writes, which is something I think all mothers can relate to. She expertly captures the beautifully dark time of new motherhood, when you’re enraptured by this tiny creature but longing for your former identity. The dynamics of grief are dealt with head on, with Schmidt unwilling to shy away from the twisted ways loss can affect mothers.

Schmidt says she drew on her own mother when writing Kitty, as well as the ways that shame can shadow a family and make a child feel responsible for fixing deep-rooted issues. I think Schmidt has done well to draw on her own experiences to create these two tragic characters in a compelling story of love, loss and letting go.

Marisa K Jones is a freelance writer who grew up between Hawaii and Australia, though if anyone asks, she doesn’t surf. Her love for travel has taken her across the world where she has written for Australian House & Garden, International Traveller and Paradise Magazine. She currently lives in Papua New Guinea with her husband and three children where she writes historical fiction novels set in PNG, exploring the truly unique country she now calls home.